To view this content, you must be a member of Crushing Krisis Patreon at $1.99 or more

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

Comic Books, Drag Race, & Life in New Zealand

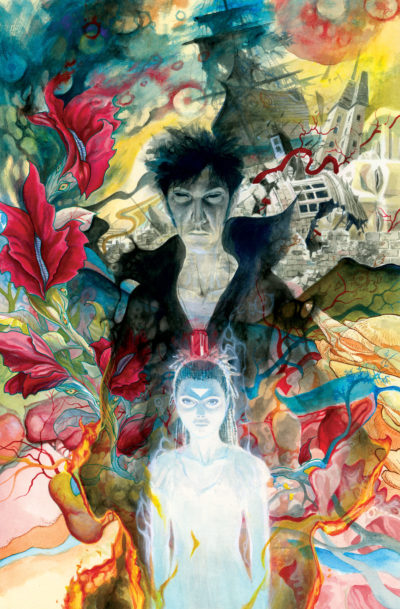

The Sandman and The Dreaming comic books definitive issue-by-issue collecting guide and trade reading order for omnibus, hardcover, and trade paperback collections. Find every issue and appearance! Part of Crushing Krisis’s Crushing Comics. Last updated June 2024 with titles scheduled for release through September 2024.

Want to get straight to reading Neil Gaiman’s legendary 75-issue Sandman series? It’s one of the most comprehensively collected runs of the past 40 years of comics, and you have plenty of format options – all explained in full below!

Read on for a history not only of Gaiman’s Sandman, but all of DC’s many Sandmen as well as the entire universe of comics that sprung from Gaiman’s work.

The Sandman is both a somewhat obscure Golden Age hero revived by the Justice Society for modern audiences and one of the most widely-read characters in the history of American comics.

They are not the same character.

The Golden Age Sandman was Wesley Dodds. Dodds was an odd early take on superheroism, dressing in a sharp green three-piece suit and subduing foes with a gun that fired gas that could compel them to tell the truth or put them to sleep.

Dodds was one of many Golden Age Justice Society characters to stay constrained to DC’s vintage Earth 2 with no Silver Age (AKA Earth 1) counterpart – although Jack Kirby and Joe Simon did briefly reinvent The Sandman in 1974 with a new character, Garrett Sanford.

In the wake of Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC could have easily reinvented either Dodds or Sanford for their new clean slate of continuity. Instead, they handed the character to a barely-known British journalist: Neil Gaiman.

Gaiman had very little work to his name at that point, including the Mostly Harmless biography of Douglas Adams and a handful of issues of 2000 AD. However, he had successfully pitched DC on a three-issue series called Black Orchid in 1988. The series didn’t sell much, but it was well-liked by editor Karen Berger. It was on the heels of that mild success that he pitched his re-imagination of Sandman.

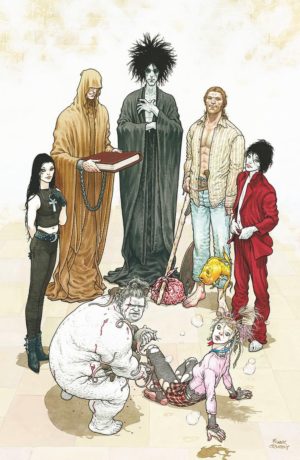

In fact, Gaiman originally intended to reference the 1970s Sandman in Black Orchid, and so his initial Sandman pitch was for that version of the character. Berger, Vertigo’s founding editor, asked him to re-pitch Sandman as a new character. In response Gaiman devised Morpheus, one of the seven eternal Endless – immutable forces of the natural world.

They rest, as they say, is history.

Sandman wasn’t an immediate pop culture force, but it caught on quickly. The first issue was popular, and sales began to climb with issue #5 and never looked back. Morpheus appeared in the other proto-Vertigo titles in Swamp Thing #84 and Hellblazer #19. Later, Gaiman began to incorporate the history of the Golden and Bronze age Sandmen into his story.

The title achieved its cultural impact by degrees over the course of the next three years until The Sandman (and Neil Gaiman, along with it) reached a tipping point and broke through into the consciousness of the wider public.

In 1990, Gaiman penned The Books of Magic mini-series for Vertigo. This self-contained low fantasy story, to which Harry Potter bears a more-than-striking similarity, proved to be a massive hit that spawned its own franchise of titles (visit the guide). Shortly before that, Gaiman and Terry Prachett released the novel Good Omens. Prachett was much more famous than the neophyte Gaiman (it was his first novel), and the book was popular.

Books garnered critical attention and Omens nabbed some significant fantasy award nominations in 1991. Perhaps uncoincidentally, so did Sandman. Issue #19, a loose adaption of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, won the World Fantasy Award in 1991 for “Best Short Fiction” (after which comics were outlawed from winning in that category).

Also in 1990, DC published the Sandman trade paperback – A Doll’s House – which originally collected issues #8 (Death’s debut) through #16. It was a massive success, and DC followed it with Preludes and Nocturnes in 1991 just as Sandman won the World Fantasy Award.

The trade paperbacks were available in traditional bookstores, where the series was discovered by audiences that the comic alone would never be able to reach. This, along with Watchmen and several of DC’s famous Batman graphic novels, were effectively the origin story of the modern American trade paperback format.

Finally, in the first week of 1992, Tori Amos’s Little Earthquakes was released. Its track “Tear In Your Hand” saying, “If you need me, me and Neil’ll be hanging out with The Dream King.”

Amos’s music garnered a cult following with literary-minded freaks and geeks on the fringes of grunge culture. As her audience devoured the dense mythology of her confessional and sometimes-fantastical lyrics, they stumbled upon Gaiman’s Sandman – as well as his pair of Death mini-series in the early 90s. Amos penned the introduction to the collection of The High Cost of Living. This brought even more fans from outside of the worlds of comics and fantasy to Gaiman’s work.

From that point forward, The Sandman was an unstoppable juggernaut of critical praise and sales … right up until Gaiman stopped it, in March of 1996 with issue #75. It ended while still outselling most of the DC line, including comics from Batman and Superman.

Gaiman had long seeded his narrative with hints of Morpheus’s end, though that didn’t necessarily mean that Sandman itself would end along with him. The end of Sandman lead to a trio of spinoffs – a second Death mini series (The Time of Your Life), a mini-series for Destiny (A Chronicle of Deaths Foretold), and the ongoing comic The Dreaming depicting the ongoing life of the dreamworld after Morpheus’s depature.

The Dreaming ran for five years, though it was never a hit on the magnitude Sandman itself. Yet, its endurance allowed for the launch of several mini-series – some under the title “The Sandman Presents.” One of those mini-series starred Gaiman’s version of Lucifer as penned by Mike Carey, which spun into its own franchise with a 75-issue series in 2000 and a later 2016 revival (visit the guide).

While the character of Sandman is wholly-owned by DC, they have always shown Gaiman an extraordinary amount of deference in their use of the universe and its characters (as opposed to, say, their treatment of Alan Moore). DC continued to release titles in this extended Sandman Universe through 2014, always with Gaiman’s consent but rarely with him writing, save for Dream Hunters and Endless Nights. That changed in 2013, when Gaiman returned not only to his Sandman Universe, but to Morpheus himself with The Sandman Overture. Overture was a tale of Morpheus’s journey prior to The Sandman #1 with lush illustrations from JH Williams and Dave Stewart.

After a several years break from any Sandman Universe stories save for Lucifer, Dream made a surprising appearance in the 2017-18 line-wide event Metal as a sort of ephemeral shepherd to Bruce Wayne. While not directly linked to the events of Metal, Dream’s appearance there can be seen as a prelude to the 2018 relaunch of the Sandman Universe as its own self-contained line of Vertigo titles beginning with The Dreaming, House of Whisper, and relaunches of Lucifer and Books of Magic. [Read more…] about The Sandman Universe – The Definitive Collecting Guide and Reading Order